The Problems With Hebrew Class

April 17, 2015

An elephant lives in JDS. It’s big, and it’s ugly, and it sneaks around the 300s, sticking its trunk into classes of students with vacant stares and deaf ears.

Nobody wants to talk about the elephant in the classroom.

Anybody who has ever studied Hebrew on the intermediate or lower levels knows that the experience isn’t anything to write to Israel about, partly because students probably don’t have the Hebrew skills necessary to write a fluent letter, and partly because the lower Hebrew classes almost without exception limp along at a pace slightly less exciting than that of a snail’s.

Yet nobody complains— or, if they do, that’s all they do, complaining to their classmates without trying to be heard or somehow bring about change. Either through some spectacular ignorance on the part of the JDS administration, or through some unspoken agreement between faculty and students, the current abysmal state of Hebrew classes has somehow become accepted as the norm at JDS.

These classes barely increase in difficulty, or cover new subject matter, even between high school and middle school classes. Actually, I’ve had essentially the same experience in all three years of intermediate-level Hebrew class at JDS.

The first half of the class is plagued by poor discussions in which students either blatantly ignore the teacher or are unable to follow along because of the often completely random nature of the discussions, each of which tends to have absolutely no connection to the one before it.

The second half of the class tends to be devoted to assignments analyzing the discussion nobody was paying attention to in the first place, engaging questions which pose the character-building challenge of completing one’s work in google translate without the teacher noticing.

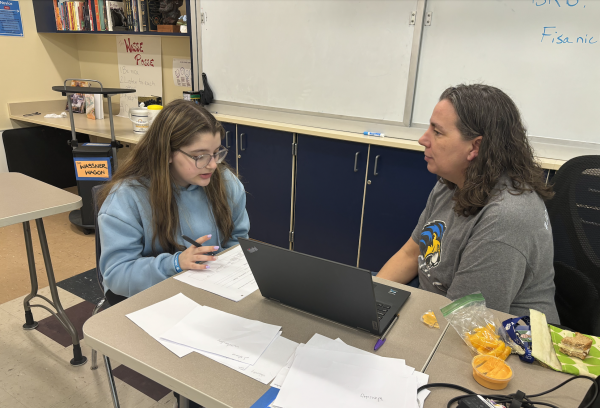

When Hebrew classes do cover the grammatical nuts-and-bolts of the language itself, sometime around the middle of the year, the indifferent students have lost too much interest in the class itself to take it seriously and the students who care struggle to memorize everything in an uphill battle against a toxic learning environment in which the teacher tries time and time again to involve students who do not want to be in the class.

A large part of the student body has had the same general experience I have had in studying Hebrew at JDS, but students studying a language other than Hebrew, such as Arabic or Spanish, might find it difficult to believe that the state of these classes is so desperate.

When discussing their overall experience in class, and how engaged they felt in the learning process, students who take advanced Hebrew classes, or alternative languages such as Arabic, expressed overall excitement and and contentment with their class, and said they feel motivated to work hard in the classroom.

It should be said, first and foremost, that this isn’t completely the fault of the Hebrew department or its members, who as often as not are completely dedicated to their students. After all, they’ve been given the near-impossible task of educating students who don’t want to participate, of keeping students interested in a curriculum that they’ve already seen, and rejected, in earlier years.

Nor is it completely the fault of the students who, finding themselves in a class they didn’t really choose, can’t bring themselves to take the class seriously.

It’s the fault of the JDS community in general, the fault of every one of us who has sat in these classes after the busywork was finished and simply waited out the clock, resigned and past caring about their neighbors asking for help. It’s the fault of the faculty who celebrate JDS’s preservation of Jewish identity, but turn a blind eye to the school’s inability to teach the Jewish language.

It’s our fault when we roll our eyes at the absurdity of the situation, and complain to our friends in the halls, but come back the next day, and the next day after that, ready for more, because no one ever seems to care enough to try to push for change.

If we, as a community, don’t talk about these issues or attempt to fix them, then we have only ourselves to blame for weak classes becoming the standard. Therefore, it is equally our responsibility to discuss the issue, to do our best as a community to fix the classes.

We need to talk about the elephant in the classroom.